Culture Whisper Review: Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album, Courtauld ★★★★★

Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album, Courtauld: monstrous nightmares and leering old crones come to life at this fantastic new exhibition

Francisco Goya biography

The famed Spanish court painter was at the height of his power in 1783, when he began to craft 8 albums of some 550 drawings. Having gone completely deaf after a terrible illness, Goya was determined to prove his skills had not waned. A snapshot of the results is on display in the fabulous new Courtauld Gallery Goya exhibition, where nightmarish old crones and haggard figures stumble across the pages of his folio drawings.

Francisco Goya (1746-1828), Cantar y Bailar (Singing and dancing), c.1819-23 London, The Courtauld

Goya exhibition, Courtauld

The Courtauld Gallery exhibition 2015 focuses on the Witches and Old Women album (1819-23) of withered hags and human folly, which, save for one work, has been gathered for the first time in its entirety. The 22 pages on display move through madness, death, erotic abandon and evil with ease and delicacy, expressing Goya’s satirical metaphors for the extremes of human perversion. Far from an exercise in simply bashing hysterical women, In these works based on the collapse of society, Goya responds to the upheaval in Europe following the French Revolution and the still rife Spanish Inquisition.

Goya exhibition 2015 – how did it happen?

Curated by Goya’s number one fan, Juliet Wilson-Bareau, and Curator of Drawings at the Courtauld Gallery, Stephanie Buck, this Goya exhibition in London has been 3 to 4 years in the making. It all began with the Courtauld Collection’s prized Goya drawing, Singing and Dancing (Page 3), a delicate print in which a gypsy floats in the air, raucously singing and playing guitar, as a second figure suggestively stares up her skirts. It has been quite a journey to gather the remaining album drawings, but the results are stunning.

Goya, London: key themes

Never meant for public display, these private works in the Goya exhibition are highly personal in their fantastical comment on human nature. Indeed in the wake of severe illness, these works allowed Goya to express his own mortality and the fear of decrepitude. With sinister themes like old age, madness, religion, dreams and superstition at play, Goya manages to maintain a satirical tone, with baffling inscriptions like Showing off? Remember your age (Black Border album no. 7, 1816-20), where a pathetic creature tumbles down a flight of stairs.

Francisco de Goya (1746- 1828), Bajan riñendo, They descend quarrelling, c. 1816-20, Private Collection

Francisco Goya artwork and technique

Goya reduces the detail of his drawings with delicate, simple marks to create a sense of space around the floating figures. With brave and dynamic watercolour brush strokes of black carbon ink, he crafts assured portraits of frightening human characters.

Goya’s grumpy old women are ironic caricatures, with sunken cheeks and grisly faces. Often tumbling through the air, the Witches and Old Women album opens with the violent They Descend Quarrelling (Page 1), which shows both a harmonious couple rising through the air while another pair plummet downwards, one tugging the hair of another whose face contorts with a painful cry. Goya viewed the physical movement of figures rising and falling as a metaphor for when things go well and poorly, and of course erotic climax.

Grimacing witches terrorise innocents in Unholy Union (Page 5), a frightening image of a witch holding aloft a terror-struck victim bound with, and Wicked Woman (Page 12). Here, a hideous creature prepares to eat a child that writhes in her arms, based on the story of two sisters in 1610 who confessed to poisoning their own children in offering to the Grand Witch Master.

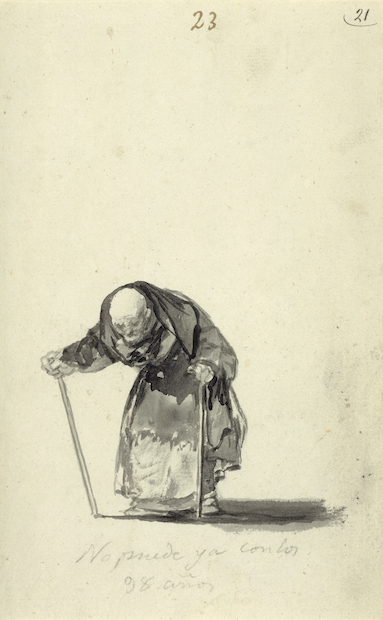

Francisco Goya (1746- 1828), He can no longer at the age of 98, c. 1819-23, J. Paul Getty Museum

You'll also find many works based on Goya's fascination with old age and the insurmountable human instinct to go on living. Look out for the stooped old women in lonely solitude as she clasps her rosary beads in She wont’ get up till she’s finished her prayers (Page 8), and old age mocking the marital dreams of a frail woman in What Folly, still to be thinking of marriage (Page 18). The final image of the album, Just can’t go on at the age of 98 (Page 23), underlines this desolation in death, as a feeble figure stumbles across the page with two walking sticks to support him.

Of course, the Goya Courtauld show can’t be taken too literally – the Spanish artist was certainly not a believer in witchcraft, and did not despise women. The works are far more complex and ironic than that. Just take a look at the toothless hag, dancing joyfully with castanets in her contentment with old age in Content with Her Lot (1816-20) from the Black Border series.

Francisco Goya, (1746- 1828), The sleep of reason produces monsters, c. 1797-98, British Museum, London.

Other Goya artist drawings

Other famous drawings from the Capricho series and Black Border album introduce the exhibition and Goya’s fascination with human frailties. Starring in the Caprichos series (1797-8) of 18 aquatints is the famous The sleep of reason produces monsters, seen here in a rare bound edition. A swarm of owls and bats surround a bent figure in sleep, the monstrous forces of his nightmares rising around him. Another drawing, which foreshadows many of the themes in the Witches and Old Women album, is the absurd old woman, preening herself before a mirror in Until Death (1797-9). As the vain old crone puckers up in front of her mirror, the maid titters behind her back.

Several works from the Inquisition album (1808-14) also offer a striking look at Goya’s nightmarish visions of abuse and torture. In These Witches Will Tell, a naked hag devours snakes as she floats through the air, a powerful example of the role of witchcraft in Goya’s imagination.

But are these nightmarish images meant to terrify our dreams? Or teach us a lesson? This exhibition of Goya’s finest drawings will certainly haunt our sleep this spring.