Culture Whisper Review: Forensics, Wellcome Collection ★★★★★

REVIEW: 'Forensics' Wellcome Collection exhibition 2015 is horribly gruesome, but a big hit for science lovers

Forensics Exhibition, London

Enter the Wellcome Collection Forensics show, a fast-paced, morbid tour of how a murder is solved. From crime scenes to the morgue and courthouse, this grisly exhibition of scientific artefacts and artworks lays bare personal stories behind death. An unforgiving and harrowing journey if you aren’t keen on the science behind crime solving, this dark exhibition nevertheless does a great job at revealing the fascinating history of Forensics in modern science.

It’s shocking to realise how recently Forensics became an established part of crime solving, and that techniques like facial recognition and criminal fingerprinting only became standard procedure in the last 100 years. The Wellcome Collection, London highlights the importance of these discoveries: from Sir Alex Jeffreys’s invention of DNA profiling, to French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon’s mug shots.

Alphonse Bertillon, CC BY: Wellcome Library, London

Bertillon was also responsible for the first ‘God’s eye view’ crime scene photos in 1901; hovering a tripod over the murder victim, Bertillon was able to reveal new evidence. Look out for macabre images by forensic photographer Angela Strassheim of private residences, where the splatters of blood from old crime scenes are revealed under BlueStar solution.

It’s easy to take these tools for granted when Benedict Cumberbatch and David Tenant are shouting about them in our living rooms: cutting edge forensics has become a cultural fascination. But of course, before Sherlock, Arthur Conan Doyle was inspired by the crime solving activities of Dr Edmond Locard at the Police Department of Lyon in France. Locard believed that details of a murderer’s identity could be found at the scene, turning to fingerprints, hairs, blood and fluids to catch himself a criminal.

Poison bottle © Science Museum, London

Gore, gore and more gore

Teenagers with a taste for the bloody will love all the guts and innards in the Morgue section of the Forensics exhibition, where gunshot wounds and decaying bodies reveal how cause of death was discovered. You won’t be able to miss the 1940s porcelain post-mortem table from Rotherhithe Mortuary in southeast London, with its central drainage hole to remove body fluids.

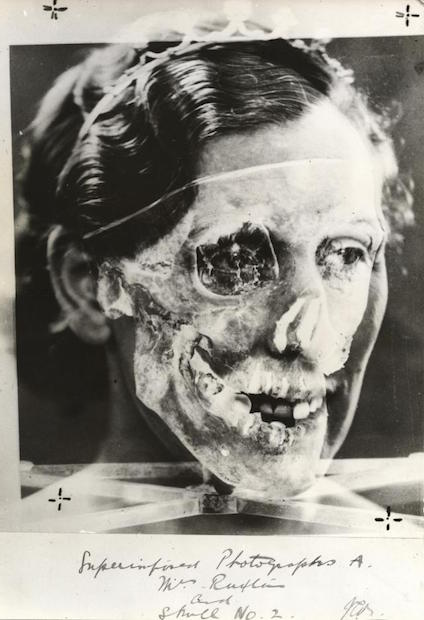

Even if you've got the strongest stomach, you might struggle with Teresa Margolles’s concrete floor (2006) where a dead body of her friend, artist Luis Miguel Suro, was discovered on the floor of his Mexico studio, and Sally Mann's harrowing image of a corpse left to decay in an open-field in the Forensic Anthropology Center of the University of Tennessee Body Farm. There’s even hideous evidence on display from the 1935 Ruxton case, where maggots collected from the human remains of Isabella Ruxton and her maid Mary Rogerson were used to discover the time of death. Another sickening moment is the collection of blowflies, which apparently deposit 250 eggs in the open wounds of a cadaver minutes after death.

Facial reconstruction of Isabella Ruxton, University of Glasgow Archive Services, Department of Forensic Medicine and Science collection

Wellcome Collection: science and art

The exhibition finds its feet in the seamless blend of science and art, with some striking photographic works next to human remains and evidence bags. A specially commissioned work by Sejila Kamenić makes a particularly jarring break in the science of it all. The intimidating silver box contains reams of information to memorialise the still-missing victims, twenty years after the Bosnian war (1992-95).

Other fascinating moments at the Wellcome Collection include a display on the invention of toxicology by Dr Mathieu Orfila and the effect of poisons on the human body. Did you know, for example, that Victorian women used to prepare arsenic as a cosmetic to lighten their skin tone? Look out for the famous case of Dr William Palmer (otherwise known as the Prince of Poisoners), who murdered his four children and friend John Cook in 1856; and the 1840 trial of Madame LaFarge, who was accused of killing her husband with the chemical. Curious tests by English chemist James Marsh helped to reveal the traces of arsenic in Charles LaFarge’s corpse and finally convict his wife.

William Hartley, Courtroom sketches of the Crippen trial at the Old Bailey, 1910 © Metropolitan Police Service

Luckily there’s some light relief from brutal deaths like the most famous London murderer, Jack the Ripper, in the Court House section; fantastic melodramatic trials are played out on the silver screen and heard in the radio play of The Black Museum to remind us why are so addicted to crime solving. A particularly rapturous line from the clipped voice of the narrator announces, 'in Scotland Yard's mausoleum of murder - here lies death'. Dramatic sketches of Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen’s 1910 trial for the murder of his wife Cora, are similarly gaudy and over the top, but a brilliant insight into the public fascination with the courthouse.

We're still wondering who is going to love this exhibition - scientists fascinated by DNA testing? Rubber neckers? But, let’s be clear, while this show is sick and twisted, and you’ll spend most of the time wincing: it’s strangely hard to tear yourself away.