The problem with TikTok's nepo baby obsession

TikTok users love to name and shame celebrities who've risen nepotistically, like Maude Apatow, Lily Rose-Depp and Daisy Edgar-Jones, but is this really productive?

There’s an eerie, cultish vibe about a lot of these posts, even the nice ones. Although many profess to love and respect actors like Daisy Edgar-Jones, whose career has ascended after starring in Normal People, users are nonetheless keen to expose them as 'nepo babies'. Edgar-Jones in particular is scrutinised because her father is a media executive at Sky Arts. It’s patronising, reductive and a bit frightening, considering how talented an actor she is.

Daisy Edgar-Jones in Where the Crawdads Sing. Photo: PA Media/Sony

Nepotism

is nothing new. Think of the Coppola family: Francis Ford

directed The Godfather and Apocalypse Now; his daughter, Sofia, directed Lost in Translation, The Virgin Suicides and On the Rocks; cousin Nicolas Cage is one of the most confusing

and brilliant actors of our time. What about Kirk and Michael Douglas; Janet Leigh and

Jamie Lee Curtis? Harry Potter himself, Daniel Radcliffe, is the son of a casting agent and a

literary agent.

Are we to dismiss all of these people, these staples of the industry? For they are talented in their fields, after all (well, Radcliffe took a while).

This is where a schism forms between 'good' and 'bad' nepo babies. Many are considered not good enough at their jobs and therefore (it's decided) they don't deserve these positions. The bad nepo babies tend to have the surname 'Beckham' or 'Kardashian'. Sons and daughters need only tell their parents their dreams, and they are fulfilled without much struggle or staying power. On the other hand, good nepo babies – like Edgar-Jones – at least have talent and have worked hard.

In film and TV, most actors and filmmakers on major productions are at least proficient in what they do – regardless of their origin stories. And when certain people lack talent on- and off-screen, their presence is not always due to mum and dad's contacts. Take Michael Bay: he's one of the highest-earning directors in Hollywood, but also one of the most critically derided. His father was an accountant and his mother was a bookshop owner/child psychologist. Does that background earn him more respect than Sofia Coppola?

Sofia Coppola directing The Bling Ring. Photo: Sky

But these TikTokkers have a point. Some of these

celebrities build a separate narrative, in which nepotism doesn't play a part. In an interview with Vogue Australia, Lily-Rose Depp (Johnny Depp's daughter) rejected the idea

that she landed roles because of who her father is… despite her first major film role

being in Kevin Smith’s Yoga Hosers, in which her father starred.

From an early age, Maude Apatow (daughter of comedy director Judd Apatow and actor Leslie Mann) starred in her father's films, including Knocked Up, This Is 40, and The King of Staten Island. She claimed in the Los Angeles Times that the exceptional teen drama Euphoria was her breakaway from her parents, proving she was ‘capable of doing work without their help’. Although Apatow is perfectly cast, the lineage probably helped her to be noticed in the first place.

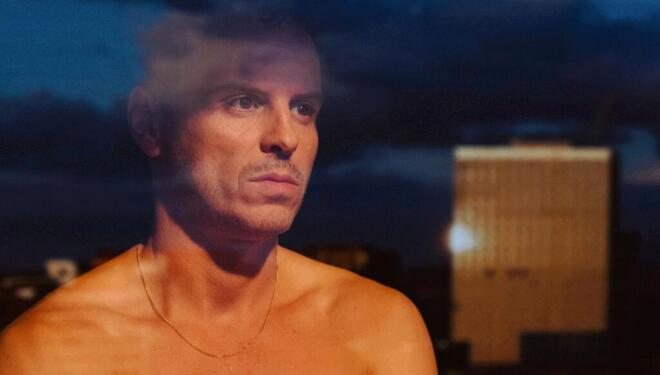

Zendaya in Euphoria season 2. Photo: Sky

It

is unfair that nepo babies can flourish quicker than those without familial connections. But this writer doesn’t believe

nepotism is the issue. Or, at least, it’s part of a whole that's even worse: talented people from less privileged backgrounds are not given the equal opportunities they deserve.

Why the obsession over naming-and-shaming nepo babies, when there are plenty of self-made celebrities to shout about? In the nicer parts of #nepobaby, there are videos devoted to this purpose. It’s a nobler effort, redirecting some rare sunshine into the blue-screen warzone of online hate.

Instead of vacuously scrutinising those who were lucky in life (it's a long list), why not celebrate those who’ve

found their way into the limelight from humbler beginnings – your Zendayas and Paul Mescals and Stephen Grahams? Social media platforms thrive on fury, so this could be another small way to battle against their digitised factory of anger.