The biggest danger of not being recognised in your own time is that you may never be recognised at all. That’s what happened to the criminally overlooked 1920s Dadaist Hannah Höch. This Spring the Whitechapel Gallery hosts the first major London exhibition of her extensive career as a collagist, and although she is finally on the verge of a permanent place in art history, these things still need a bit of shoring up.

Born in 1889 in Germany, Höch fell in with the Berlin Dadaists in 1919. Enamoured by their bold, brash, iconoclastic drive to smash social conventions, she adopted their trademark ‘photomontage’ medium and exhibited her first scathingly satirical pieces with them at the First International Dada Fair in Berlin in the 1920s.

The Whitechapel’s exhibition brings 100 of these montages together from collections scattered all over the world. Consisting of multiple photos, magazine clippings, newspaper headlines and bits of advertisements cobbled and collaged together, this is a body of work that skilfully decontructs visual culture in Germany from the 1910s up to the 1970s, homing in on the fashion industry, banking, and the military.

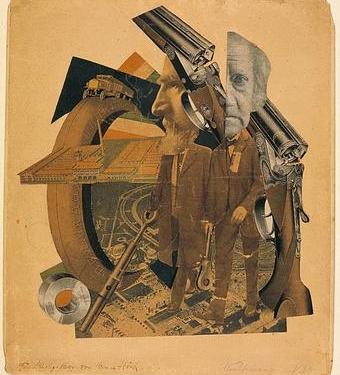

The montage Hochfinanz (High Finance, 1923) is a must-see example of the Höch-ian smash/critique: in it she throws shotguns, suited businessmen and industrial machinery together into an image that screams of the incestuous relationship between banking and the arms trade.

But like Max Ernst, who is her only serious rival with a scalpel and glue, her work went beyond even Dada. She was not content with the straightforward Dadaist ambition of being “anti-art”. Höch wanted her collages to be beautiful, if untraditionally so. They are, on the whole, chaotic but comprehensible, drawn together by a controlled colour palette or composition. They throw things together in order to ask you how they relate to each other. Men and women, crafts and art, finance and war: how do these things interact? And are we happy with the way they do it?

So far so good, but raging against the system was a man’s game, and in this final qualification Hannah Höch fell short. The Dadaists were vocal about women’s rights, but when faced with an actual woman doing actual art, they saw her greatest contribution to the movement as the ‘sandwiches, beer and coffee she managed somehow to conjure up despite the shortage of money.’ Her art attacked the continued pigeon-holing, patronising, and subjugation of women, while at the same time being pigeon-holed, patronised, and minimised by her Dada colleagues.

Later in the century she was condemned “entartet” (degenerate) and a “cultural Bolshevik” by the Nazis, and moved to the remote suburb of Berlin-Heiligensee to live out the war in secret, trying hard not to look like an artist. And so, when history was being written by New Yorkers talking to expat Dadaists and Surrealists, Hannah Höch was in hiding.

Disappointingly, a few of her best-known works, including the magnificent Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919–1920, are missing from this exhibition, presumably deemed too fragile to survive international transit (being, as they are, made of centuries-old newspaper). Nevertheless, the pieces that have made it to the Whitechapel excellently commemorate her contribution to 20th century art history, and in this, her first major exhibition in Britain, she is looking relevant as ever.

| What | Hannah Höch, Whitechapel Gallery |

| Where | Whitechapel Gallery, 72-78 Whitechapel High Street, London, E1 7QX | MAP |

| Nearest tube | Whitechapel (underground) |

| When |

15 Jan 14 – 23 Mar 14, 12:00 AM |

| Price | £9.95 |

| Website | Click here to book via the Whitechapel Gallery |