Having started life in Sheffield four years ago, this blazing, heartfelt and heartbreaking show from Richard Hawley and Chris Bush has finally made it to the West End via a stint at the National last year. Seeing it for the first time, it's easy to see why it has set such a hype train in motion.

Set on the Park Hill estate in Sheffield, a brutalist development typical of the kind that sprang up everywhere in the 50s and 60s, it charts a cycle of decline and gentrification through the eyes of three generations of residents. Young working class couple Rose and Harry are first through the door in 1960, followed in '89 by an immigrant family escaping conflict in Liberia, and finally in 2015 by a middle class Londoner hoping for a fresh start after a break up. What binds them together, beyond geography, isn't clear at first, but as their stories progress so too do the connections, building to a stunning finale that shows how their lives – and in a sense, all of ours too – are intertwined. It's about as emphatic a repudiation of Thatcher's famous line about there being 'no such thing as society' as you'll find.

A couple of original 2019 cast members have stayed with Robert Hastie's production, including Rachael Wooding, whose lovable Rose weathers the decline of her husband, steelworker Harry (Joel Harper-Jackson), who proudly claims the title of "youngest foreman in the world". Although their storyline feels a little archetypal, reminiscent of another great Sheffield export, The Full Monty, it's aptly allegorical for the city's post-industrial identity crisis.

Other stand out performances include Elizabeth Ayodele, whose exuberant teenager Joy falls for a local boy, much to the disapproval of her Guinean aunt who has been warned to lock the door to keep out bad men. Laura Pitt-Pulford is superb as the heartbroken Poppy, whose fish-out-of-water status as an Ocado-shopping southerner is the source of many of the show's biggest laughs. And her scouse ex Nikki is a smoky-voiced Lauryn Redding, whose rendition of torch song 'Open Up Your Door' sounds like a northern answer to Adele. But then again it seems unfair to spotlight particular turns in a piece that is emphatically ensemble-driven.

Bush's book skilfully balances the wider story of the block's decline and subsequent social cleansing with the personal impacts, not all of which are predictable. And though Hawley's score takes time to work its magic, with some of the early numbers feeling more album filler than killer, by the latter stages, when choral numbers blend with soaring melodies, augmented by Lynne Page's free-flowing choreography, it becomes irresistible and perfectly captures both the tragedy and joy of these 'streets in the sky'.

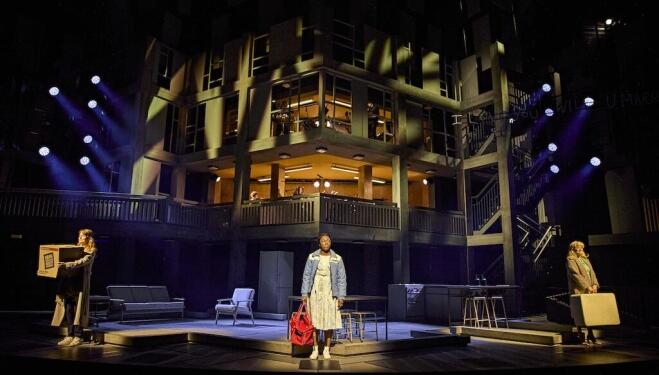

As well as being appropriately brutalist, the Gillian Lynne is a natural home for productions transferring from the Olivier, and so it proves again. Ben Stones' high-rise set, with the (excellent) band situated behind windows, fills the expansive stage, and the amphitheatre auditorium enables cast members to make occasional forays among us. The estate's iconic 'I love you will u marry me' neon sign looms over everything like a motto, or perhaps a declaration of faith. After a convoluted, pandemic-interrupted journey, it feels like the show has finally found its long-term home, and it certainly deserves a long lease.

Standing at the Sky's Edge, National Theatre review ★★★★★

By Holly O'Mahony

Three households living decades apart but united by geography are the subject of Chris Bush and Richard Hawley’s bittersweet musical Standing at the Sky’s Edge. Set on the sprawling, Grade II listed Park Hill housing estate in Sheffield, it charts the development, demise and regeneration of one of the UK’s most ambitious social housing schemes, through the interconnecting personal stories of three women and their loved ones.

Standing at the Sky’s Edge premiered at the Sheffield Crucible back in 2019, but it’s only now we’re safely on the other side of the pandemic that it’s getting to prove it’s not just a Sheffield story but one with mass appeal, and more than capable of filling the National’s Olivier Theatre.

Faith Omole (Joy) and Samuel Jordan (Jimmy) in Standing at the Sky’s Edge. Photo: Johan Persson

Bush, who has already explored the topic of Sheffield’s regeneration in her triptych of plays Rock / Paper / Scissors, has written the book for the show, and was given free rein with singer-songwriter Richard Hawley’s back catalogue to source appropriate songs. Being pre-written, the songs don’t always complement the story (and as they also don't progress the plot, this is more a play with songs than a straight-up musical), but while integrations aren't entirely seamless, they get smoother by the second half – and it's a treat to hear Hawley’s powerful ballads fill the auditorium.

Renditions of Open Up Your Door, There’s a Storm A-Comin’ and a beautifully harmonised and hopeful For Your Lover Give Some Time are especially powerful. Credit must go to the rock orchestra, visible above the stage, for adding gutsy pzazz to the musical numbers, and Lynne Page’s gentle, lilting choreography for capturing the songs’ sentiments of hope, longing to connect and desiring to be loved.

Alex Young (Poppy) in Standing at the Sky’s Edge. Photo: Johan Persson

The three women at the heart of Bush’s story, each doing their best in the face of tough personal circumstances, are easy to warm to. Rose (a vivacious Rachael Wooding), arriving on the estate in the 1960s, is an early beneficiary of the Park Hill scheme, which promised residents streets in the sky, on-site facilities and caretakers on call 24/7. Her story looks hopeful until her husband, a victim of the steel industry job cuts, turns to the bottle.

Joy (Faith Omole, stunningly good) arrives as a teenager in the late 1980s, when swathes of the complex were used to house families in need like hers, who fled the Liberian Civil War. She soon falls in love with local boy Jimmy, and their stories intertwine. Poppy (a loveable Alex Young) moves into the newly refurbished block in 2015, following a break-up. A gentrifier with good intentions, she’s keen to swap London hostility for northern hospitality, even if her neighbours raise their eyebrows at her Ocado deliveries and offering of gluten-free cookies.

The Company of Standing at the Sky’s Edge. Photo: Johan Persson

On Ben Stones’ set, where the exterior of the brutalist Park Hill complex looms in the background, and a stringy, neon relic of a graffitied proposal ‘I love you will u marry me’ hangs above, director Robert Hastie has the three generations occupy their flat simultaneously. It’s moving watching them unpack belongings, lay the kitchen table and cook dinner (Rose’s shepherd’s pie coming out of the same oven as Poppy’s Ottolenghi recipe), oblivious to one another, with Sheffield’s staple condiment, Henderson's Relish, seemingly the only throughline.

More connections between the generations soon surface, and even if their stories are tied together a little too neatly, it’s impossible not to invest in their outcomes – rooting for some, feeling anguished for others.

A songful love letter to the UK’s crippled social housing sector, Standing at the Sky’s Edge deserves to run and run and run.

| What | Standing at the Sky’s Edge, Gillian Lynne Theatre review |

| Where | The Gillian Lynne Theatre, 166 Drury Lane, London, WC2B 5PW | MAP |

| Nearest tube | Tottenham Court Road (underground) |

| When |

08 Feb 24 – 03 Aug 24, 7:30 PM – 10:00 PM |

| Price | £24+ |

| Website | Click here for more information and to book |