The curtain goes up on Danses Concertantes to reveal a striking stylised Greek frieze peopled by outlandish colourful birdlike figures.

Kenneth MacMillan, Danses Concertantes, The Royal Ballet © 2024 Tristram Kenton

Created in 1955, this was the young MacMillan’s first work for Sadler's Wells Ballet Theatre (now BRB), and he set it to Stravinsky’s eponymous chamber piece with its evocative jazz influences. Daringly costumed by Nicholas Georgiadis in his first collaboration with MacMillan, this is a work of its time, yet its jazzy, jagged and restless movements – fingers splayed, the line of the arms broken at the elbow, hips wiggling – feels intensely modern.

On opening night Vadim Muntagirov and Isabella Gasparini led a cast of six soloists backed by an ensemble of six women in a performance that could perhaps have been a tad crisper. I would also quibble with the headpieces that made the men in particular look a little silly.

The second piece of the programme, Different Drummer, couldn’t have been more different. It is MacMillan's take on Georg Büchner's play Woyzeck, the harrowing, unremittingly grim story of a simple soldier driven to madness and the murder of the only person he loves, his wife Marie, by his inhumane treatment at the hands of experimenting army doctors.

Set to Webern’s 'Passacaglia Op 1' and Schoenberg’s 'Verklärte Nacht', it was originally created for The Royal Ballet in 1984.

MacMillan uses the language of German expressionism to shape vivid characters from the grotesquely sinister Captain, a great turn by Thomas Whitehead, to Woyzeck, a memorable, deeply moving performance by Marcelino Sambé.

Marcelino Sambé and Francesca Hayward in Different Drummer, The Royal Ballet © 2024 Tristram Kenton

Sambé’s expressive body gradually curls in on itself – a simple man defeated, finding his only consolation in Marie, a convincingly fragile Francesca Hayward, until she betrays him with the Drum Major, danced by Francisco Serrano, whose explosive vitality contrasts painfully with Woyzeck’s broken spirit.

It’s a haunting piece, containing many of the themes that would recur in the MacMIllan canon.

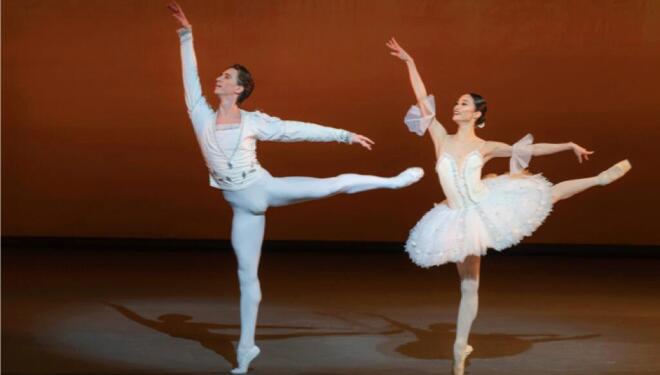

The final piece, Requiem, set to Fauré’s mass of the dead, fills the stage with intense ethereal beauty, the sorrow of death gradually appeased on the path to paradise.

Its look eschews materiality: it’s danced against unintrusive translucent pillars, the dancers in designer Yolanda Sonnabend’s gleaming pale bodystockings with splashes of muted colour across the torso.

Melissa Hamilton and artists of The Royal Ballet in Requiem. The Royal Ballet © 2024 Tristram Kenton

Created in 1976 for Stuttgart Ballet, MacMillan’s Requiem became a memorial for John Cranko, the influential director whose death the company was still coming to terms with.

Lauren Cuthbertson danced with great authority as the consoling female figure who leads the ensemble towards acceptance; her unhurried pas de deux with Matthew Ball drawing unhurried, sumptuous lines. Melissa Hamilton stood out as the second female lead; and there was classy dancing from Joseph Sissens (surely on the path to promotion) and Lukas B. Brændsrød.

A final word of praise for the Royal Opera Chorus and the two outstanding soloists: soprano Isabella Díaz and baritone Joseph Jeongmeen Ahn, as well as for the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House conducted by Koen Kessels.

| What | The Royal Ballet, MacMillan Triple Bill Review |

| Where | Royal Opera House, Bow Street, Covent Garden, London, WC2E 9DD | MAP |

| Nearest tube | Covent Garden (underground) |

| When |

20 Mar 24 – 13 Apr 24, 19:30 Dur.: 2 hours 45 mins inc two intervals |

| Price | £40-£110 |

| Website | Click here to book |