Dancers in lockdown

Culture Whisper talks to Marcelino Sambé and César Corrales, two of the Royal Ballet’s golden generation of male dancers featured in the BBC’s forthcoming documentary Men at the Barre

Marcelino Sambé in Don Quixote © ROH 2019. Photo: Andrej Uspenski; César Corrales in Bluebird © ROH 2019. Photo Helen Maybanks

They couldn't be more different. One was born into a humble family of African migrants in the suburbs of Lisbon, and had never even seen a ballet when he auditioned to enter the Portuguese Conservatoire; the other was born to Cuban ballet dancer parents and grew up in a ballet millieu, his destiny traced from birth.

One is an out gay man, whose partner is a lawyer; the other lives with the Royal Ballet principal ballerina, Francesca Hayward.

César Corrales as Romeo and Francesca Hayward as Juliet in Romeo and Juliet, The Royal Ballet © ROH 2019. Photo: Helen Maybanks

One speaks with fizzing vitality, thoughts pouring out and sometimes tripping over each other, in contrast with the laidback gentle Cuban drawl of the other.

And yet they have one fundamental thing in common: both are thrilling, dynamic, breathtaking performers, part of a golden generation of male ballet dancers in their early to mid-20s, who are bringing renewed sparkle to the performances of Britain’s premier company, The Royal Ballet.

They are Marcelino Sambé, The Royal Ballet’s newest male principal, and César Corrales, a first soloist insistently knocking at the door of the company’s top rank.

Sambé and Corrales are featured in the BBC’s forthcoming documentary Men at the Barre, which goes behind the scenes to find out what makes a great male dancer and, more importantly perhaps, to challenge the narrow concept of masculinity that still defines prevailing views of male dancers.

The sort of views, in fact, that meant that as children both Sambé and Corrales were bullied for wanting to dance.

‘When I started doing dance I was the only boy in this African dance group,’ Marcelino Sambé told Culture Whisper, ‘but I was incredibly protected by the girls, I knew the girls loved me, so I felt very comfortable there; but outside I was a bit of an outsider, didn’t feel comfortable among the other boys playing football, I felt like they always put me on the spot.’

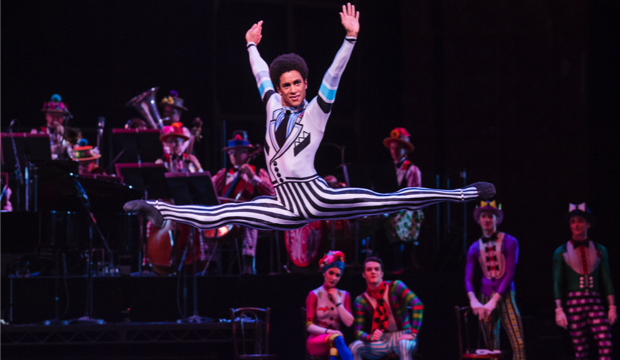

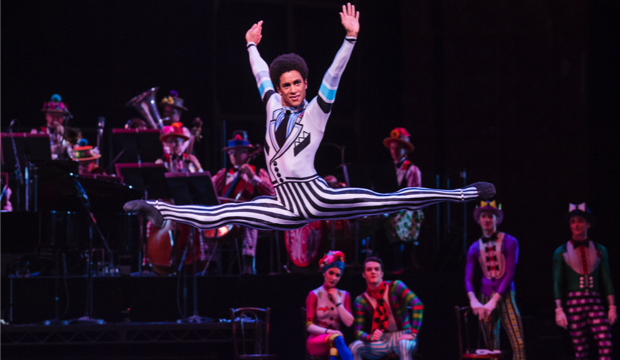

Marcelino Sambé in Elite Syncopations, The Royal Ballet © ROH 2018. Photo: Tristram Kenton

César Corrales, too, has memories of bullying: ‘For sure, I was bullied, but the difference with me is I grew up in a ballet family, so I was involved in the company, I knew really the value of it. For me, being a ballet dancer was not something I saw in the distance, or something I wished I was, because I had it all right in front of me. So the bullying didn’t affect me too much. If anything, it gave me more energy to become what I am today.’

In conversation with César Corrales, the word ‘knowledge,’ or lack of it, recurs. Asked about the persistent misconceptions and prejudice surrounding male dancers, he answers:

‘I think we need to give people the knowledge about male dancing, I think there’s just so much misconception, and also sometimes, for example, a TV advert that does us no favours, but we cannot do anything about that, all we can do is to show the real thing. There’s always going to be the lack of knowledge, obviously, so the more that we can show, the better.’

Marcelino Sambé’s answer to the same question is fuller, more passionate:

‘That is so important right now, and there’s this revolution about what is masculinity, what being a man really is in all aspects, [what is] being human, whether man or woman. [There is] more comprehension, more openness, we now see more queer references in all art areas; and it’s so important to see we are all human and equal. I feel like now it’s such a special time because we are fighting the preconceptions that men can only be one way, there are so many more interesting ways [of being].’

Men at the Barre touches on the need for ever-growing diversity in ballet, to push the art form away from a mere middle-class pursuit to one with the potential to turn lives around.

‘I think there needs to be the opportunity for people who just cannot make it, who can’t always pay the fees, don’t have the connections,’ César Corrales told us. ‘For example, in Cuba there were so many kids from the streets, it was like a hidden talent, and if it weren’t for free school for ballet, they wouldn’t be able to find that talent. In my opinion, it should be about giving them the opportunity to show themselves and to bring to the table what they can do.’

Marcelino Sambé says he’s a prime example of what ballet can mean in a young life.

‘I come from a humble background, I had no family experience of ballet, I‘d never seen a ballet when I auditioned for the Conservatoire, and they discovered something unique about me, so special, it made feel me feel so important, for the first time I had people looking at me like I had something special.’

From the point of view of the audience he does indeed have something special: an effervescent stage presence, a powerful jump, graceful movements and an engaging sunny smile. He’s modest, though, saying that every single one of his generation of dancers has something special; what is special about himself, he feels, is his versatility.

‘I wasn’t someone who only wanted to do classical or contemporary,' he says. 'I wanted to do both and be in a company where I could really do both techniques and perform both styles. So one night do Swan Lake and the next do Crystal Pite or Cathy Marston, that’s what I hope I can do more and more of.’

Marcelino Sambé and Lauren Cuthbertson in Cathy Marston's The Cellist © ROH 2020. Photo: Bill Cooper

As a Cuban, César Corrales, likes to ‘give that small flavour of the Latin side,’ and in the documentary is seen demonstrating a short virtuoso variation. It looks just a touch like showing off… but he insists he doesn’t put it on, rather: ‘whatever comes across is natural.’

César Corrales as Lescaut, Mayara Magri as Lescaut's Mistress in Manon © ROH 2020. Photo: Bill Cooper

We spoke, of course, on the phone; like the rest of us, these dancers have been in lockdown. Deprived of their demanding daily routine, they’re trying to keep their bodies fit and their spirits up – not easy. They do the daily Royal Ballet company class with the help of Zoom, but as Marcelino puts it: ‘my flat is not as big as a studio in the Opera House. There’s barely a place to jump or do challenging steps.’

Corrales says he’s lucky to have a yoga studio underneath his flat, where he has a barre and the space to practise and, of course, it helps to live with a fellow dancer.

‘For sure it makes a massive difference: me and Frankie we train together, we can do partnering, it really keeps us going rather than having to do all of this on your own. Sometimes we just fool around, we do some pirouettes, we do some lifts.’

It will be some time before Marcelino and César can go back to do what they do best – dance, and with their art help dispel narrow-minded views of men in ballet.

Men at the Barre: Inside the Royal Ballet is broadcast on BBC Four on 27 May at 9pm.

Read Culture Whisper's review here.

One is an out gay man, whose partner is a lawyer; the other lives with the Royal Ballet principal ballerina, Francesca Hayward.

César Corrales as Romeo and Francesca Hayward as Juliet in Romeo and Juliet, The Royal Ballet © ROH 2019. Photo: Helen Maybanks

One speaks with fizzing vitality, thoughts pouring out and sometimes tripping over each other, in contrast with the laidback gentle Cuban drawl of the other.

And yet they have one fundamental thing in common: both are thrilling, dynamic, breathtaking performers, part of a golden generation of male ballet dancers in their early to mid-20s, who are bringing renewed sparkle to the performances of Britain’s premier company, The Royal Ballet.

They are Marcelino Sambé, The Royal Ballet’s newest male principal, and César Corrales, a first soloist insistently knocking at the door of the company’s top rank.

Sambé and Corrales are featured in the BBC’s forthcoming documentary Men at the Barre, which goes behind the scenes to find out what makes a great male dancer and, more importantly perhaps, to challenge the narrow concept of masculinity that still defines prevailing views of male dancers.

The sort of views, in fact, that meant that as children both Sambé and Corrales were bullied for wanting to dance.

‘When I started doing dance I was the only boy in this African dance group,’ Marcelino Sambé told Culture Whisper, ‘but I was incredibly protected by the girls, I knew the girls loved me, so I felt very comfortable there; but outside I was a bit of an outsider, didn’t feel comfortable among the other boys playing football, I felt like they always put me on the spot.’

Marcelino Sambé in Elite Syncopations, The Royal Ballet © ROH 2018. Photo: Tristram Kenton

César Corrales, too, has memories of bullying: ‘For sure, I was bullied, but the difference with me is I grew up in a ballet family, so I was involved in the company, I knew really the value of it. For me, being a ballet dancer was not something I saw in the distance, or something I wished I was, because I had it all right in front of me. So the bullying didn’t affect me too much. If anything, it gave me more energy to become what I am today.’

In conversation with César Corrales, the word ‘knowledge,’ or lack of it, recurs. Asked about the persistent misconceptions and prejudice surrounding male dancers, he answers:

‘I think we need to give people the knowledge about male dancing, I think there’s just so much misconception, and also sometimes, for example, a TV advert that does us no favours, but we cannot do anything about that, all we can do is to show the real thing. There’s always going to be the lack of knowledge, obviously, so the more that we can show, the better.’

Marcelino Sambé’s answer to the same question is fuller, more passionate:

‘That is so important right now, and there’s this revolution about what is masculinity, what being a man really is in all aspects, [what is] being human, whether man or woman. [There is] more comprehension, more openness, we now see more queer references in all art areas; and it’s so important to see we are all human and equal. I feel like now it’s such a special time because we are fighting the preconceptions that men can only be one way, there are so many more interesting ways [of being].’

Men at the Barre touches on the need for ever-growing diversity in ballet, to push the art form away from a mere middle-class pursuit to one with the potential to turn lives around.

‘I think there needs to be the opportunity for people who just cannot make it, who can’t always pay the fees, don’t have the connections,’ César Corrales told us. ‘For example, in Cuba there were so many kids from the streets, it was like a hidden talent, and if it weren’t for free school for ballet, they wouldn’t be able to find that talent. In my opinion, it should be about giving them the opportunity to show themselves and to bring to the table what they can do.’

Marcelino Sambé says he’s a prime example of what ballet can mean in a young life.

‘I come from a humble background, I had no family experience of ballet, I‘d never seen a ballet when I auditioned for the Conservatoire, and they discovered something unique about me, so special, it made feel me feel so important, for the first time I had people looking at me like I had something special.’

From the point of view of the audience he does indeed have something special: an effervescent stage presence, a powerful jump, graceful movements and an engaging sunny smile. He’s modest, though, saying that every single one of his generation of dancers has something special; what is special about himself, he feels, is his versatility.

‘I wasn’t someone who only wanted to do classical or contemporary,' he says. 'I wanted to do both and be in a company where I could really do both techniques and perform both styles. So one night do Swan Lake and the next do Crystal Pite or Cathy Marston, that’s what I hope I can do more and more of.’

Marcelino Sambé and Lauren Cuthbertson in Cathy Marston's The Cellist © ROH 2020. Photo: Bill Cooper

As a Cuban, César Corrales, likes to ‘give that small flavour of the Latin side,’ and in the documentary is seen demonstrating a short virtuoso variation. It looks just a touch like showing off… but he insists he doesn’t put it on, rather: ‘whatever comes across is natural.’

César Corrales as Lescaut, Mayara Magri as Lescaut's Mistress in Manon © ROH 2020. Photo: Bill Cooper

We spoke, of course, on the phone; like the rest of us, these dancers have been in lockdown. Deprived of their demanding daily routine, they’re trying to keep their bodies fit and their spirits up – not easy. They do the daily Royal Ballet company class with the help of Zoom, but as Marcelino puts it: ‘my flat is not as big as a studio in the Opera House. There’s barely a place to jump or do challenging steps.’

Corrales says he’s lucky to have a yoga studio underneath his flat, where he has a barre and the space to practise and, of course, it helps to live with a fellow dancer.

‘For sure it makes a massive difference: me and Frankie we train together, we can do partnering, it really keeps us going rather than having to do all of this on your own. Sometimes we just fool around, we do some pirouettes, we do some lifts.’

It will be some time before Marcelino and César can go back to do what they do best – dance, and with their art help dispel narrow-minded views of men in ballet.

Men at the Barre: Inside the Royal Ballet is broadcast on BBC Four on 27 May at 9pm.

Read Culture Whisper's review here.

TRY CULTURE WHISPER

Receive free tickets & insider tips to unlock the best of London — direct to your inbox