This is the first chance the public has had to see the work of American artist Georgia O’Keeffe in a British gallery in over 20 years.

And there is no more fitting host than the Tate Modern. Its recent extension includes more female artists than ever. Following exhibitions of Yayoi Kusuma and Agnes Martin, Frances Morris, the Director, continues to honour women.

To Morris it’s an “incredibly revelatory installation”. Revelatory it certainly is for those who thought O’Keeffe was either brazenly or innocently preoccupied with painting sexually suggestive flowers: they make up less than 5% of O’Keeffe’s artistic output. Nevertheless, they have defined her in the public imagination, not least Jimson Weed, which broke all records for the sale of a painting by a female artist in 2014 when it sold for $44.4 million, more than twice the previous record. It's in the small room dedicated to O'Keeffe's flower paintings.

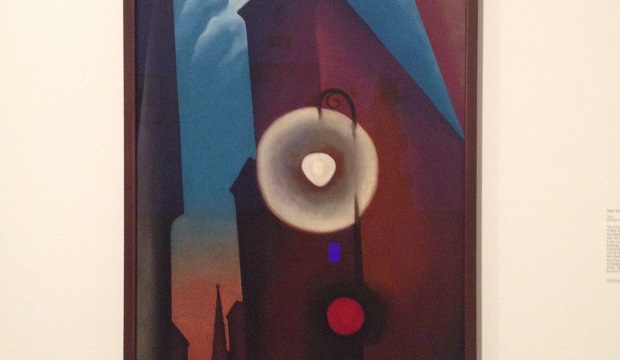

Yet O’Keeffe was so against the Freudian interpretations of these works that she promptly moved to paint the New York cityscape instead. Her best cityscape in this exhibition uses a pleasing bud-like streetlamp as a focal point.

“They’re really talking about their own affairs,” she said of those who tried to read her sexuality in the language of flowers.

The curators are so keen to support O’Keeffe’s own voice that the exhibition shop sells a kind of ‘anti-flower’ mug: a quote about flowers adorns a green mug, but no flower image – eschewing the easy decorative option for a strong statement. A quote from O’Keeffe introduces each room and she proves an eloquent guide.

Not just flowers: O'Keeffe explores the Southwest of the States and Native American culture, here with eagle claw and beans

Her photographer husband, Albert Stieglitz, was the first to exhibit her work. He provides a lens through which we see the artist. His portraits of O’Keeffe, including some erotic images, show O’Keeffe cutting a dramatic figure against the landscape of her own works.

Husband and wife for two decades, they shared subject matter and this allows us to see the revelation that O'Keeffe was: compare O'Keeffe’s interpretation of clouds to her husband’s camerawork – he is limited by the fledgling craft to small monochrome works, whilst she rejoices in the ability of her own painting to transcend what she actually saw.

O'Keefe's 'Celebration', painted shortly after marriage alongside her husband's cloud photographs

O'Keeffe was interested in synaesthesia (the ability to see sound) like Kandinsky, who painted ‘compositions’ based on music. The second room of the exhibition shows the problem O’Keeffe faced: pretty pastel folds and waves could easily be seen as abstract florals by those keen to push a Freudian agenda, but they could actually represent sound waves.

So what’s left when we uproot this feminist interpretation, as difficult to shift as Jimson Weed? We get American apples, desert doorways, bleached bones and pleasingly creased landscapes.

After a disappointingly drab first room, the exhibition unpacks O’Keeffe. She loved the landscapes of New Mexico and painted series after series of their creased hills. The final room shows her biggest, most abstract landscapes as seen from planes. These last paintings come from a place of high freedom, a metaphoric escape from interpretation. The abstract The Sky Above The Clouds is dreamy, escapist and excellent.

Because we are used to the bombastic and suggestive, the reality of O’Keeffe is somewhat disappointing – the works are smaller for not all being larger-than life flowers. Instead we have light, dreamlike landscape where bones are just bones, painted because she liked their shapes.

It’s greater in scope, more complex, more interesting. We’ve lost a brazen feminist icon and found an artist.

| What | Georgia O'Keeffe, Tate Modern |

| Where | Tate Modern, Bankside, London, SE1 9TG | MAP |

| Nearest tube | Southwark (underground) |

| When |

06 Jul 16 – 30 Oct 16, 10.00–18.00 Sunday – Thursday, 10.00–22.00 Friday – Saturday |

| Price | £19 |

| Website | Click here for more details |